Case studies: Beyond the Campus

The Institute of Contemporary Arts London Student Forum: Debates on Radical Education

The ICA Student Forum: Informal Learning

With the ICA Student Forum the Institute of Contemporary Arts London (ICA) actively engages students in collectively curating a public programme of events in response to the ICA programme of exhibitions, films, performances and public events. The Student Forum was established in 2010 with the aim of offering students the opportunity to develop conceptual and practical skills in curating fine art and managing events at a high profile arts institution. Current participants range from BA and MA students in the fields of Fine Art, Curating Contemporary Art and Performing Arts among others, to PhD students in various culturally engaged subjects. The purpose of the Student Forum is to continue a long-term engagement between the ICA and young emerging practitioners. As a multi-disciplinary art institution that has been at the forefront of radical art practices, the ICA is committed to maintaining an active dialogue with a body of students engaged in critical thinking around contemporary practice and notions of informal learning, as well as formulating new ideas and theories in response to the ICA programme (leading also towards the publication of critical texts). Every year the ICA hosts the acclaimed Bloomberg New Contemporaries (BNC) exhibition, which showcases a selection of the best visual art graduates from British Art Schools. New Contemporaries is an organisation that works to support emerging artists at the beginning of their careers by introducing them to the visual arts sector and to the public through a variety of platforms, including an annual exhibition at the ICA. Artists, whether still studying or having recently graduated, are given opportunities to make contacts and gain professional experience outside of their educational institutions. For the annual exhibition, artists are invited to submit a portfolio of work, from which a selection is made by a panel of judges. The selection is made by artists and writers, and often the selector will have previously been exhibited in a New Contemporaries show. Founded in 1949 as the 'Young Contemporaries', the exhibition has run annually as a means to provide an impartial and democratic stepping stone from arts education to the professional art sector. The 2-month BNC showcase is accompanied by reading groups and workshops jointly organised by the ICA Student Forum and exhibiting artists. This allows for critical debate between students, recent graduates and professional artists within the framework of an institution that is actively encouraging the discussion of radical artistic practices and alternative learning. In an effort to renew the discourse around Higher Education in the Cultural and Creative Industries, the Student Forum has organised a Radical Education Workshop on Saturday, 18th Jan 2014. Inline with the BNC and the Student Forum activity, which highlights the importance of bohemian graduates for a continuity of radical artistic practices, this event called into the attention the urgency of rethinking arts education – especially in times when soaring tuiton fees and increasing professionalisation of artistic practices decrease artistic autonomy. |

Related case studies

Radical Education Links:

ICA Student Forum Events Open School East Learning from Kilburn Radical Education Forum Press coverage: The Guardian: Let's change the world for arts students in 2014 |

Radical Education Workshop: Report

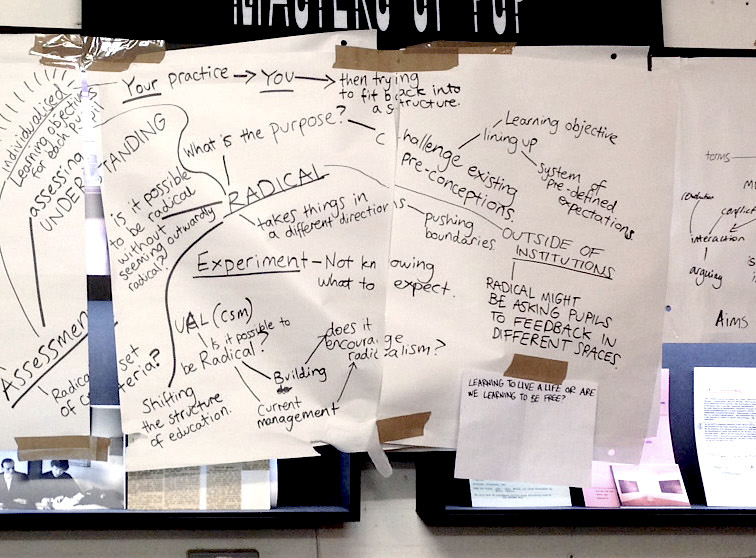

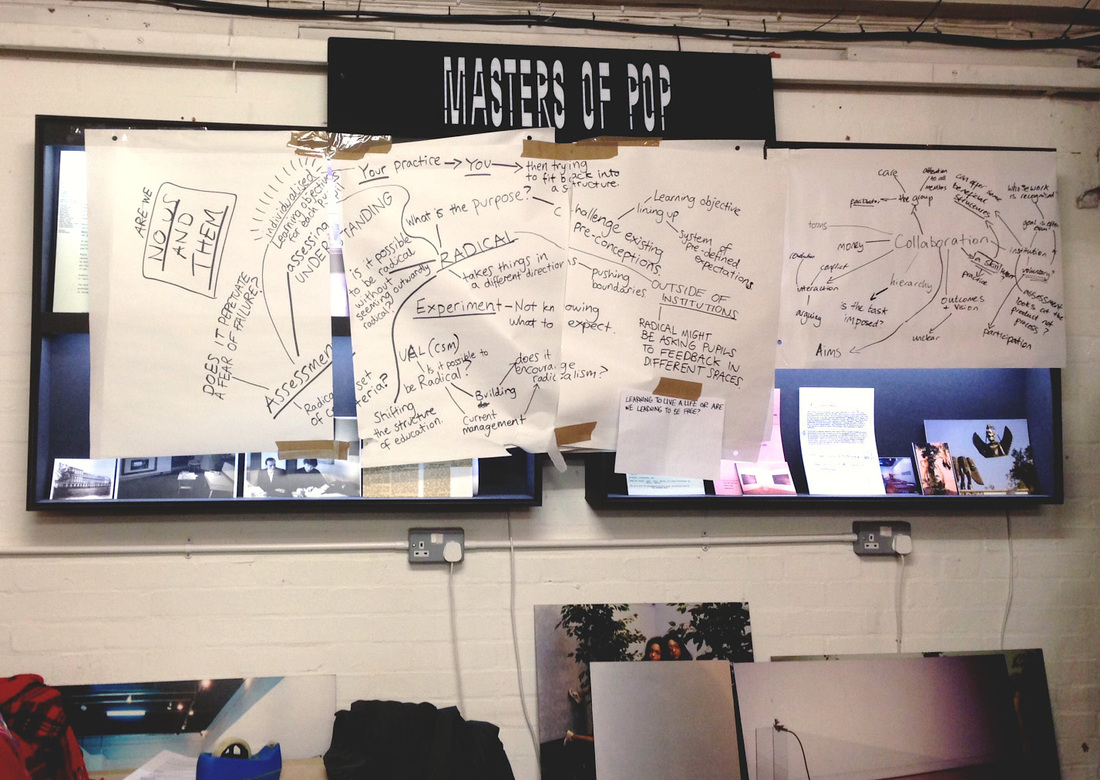

The 2 hour workshop focused on 3 main questions (see below) which were discussed in 3 separate groups of roughly 15 participants each. The first task was to discuss the designated topic in the group and then present the findings to the entire workshop panel with the help of a mind map.

Group 1) – What does it mean to put a monetary value on education?

This group discussed the importance of accessibly to and independence of arts education on the backdrop of soaring HE fees. The monetary value of arts education raises questions about the autonomy of how artistic knowledge is mediated. The Barbican in London for example supports the development of an East London alternative art school called Open School East which was launched in September 2013. Some participants criticised that this would increase the Barbican's cultural power by crucially determining the schools development (However, in what ways this influences the teaching curriculum and knowledge exchange structure is still to be evaluated). With this in mind some participants have argued that there should be the possibility for alternative or even free forms of creative HE. There was a strong consensus that the precarious work structures artists are exposed to after graduation put them at strong disadvantage compared to peers graduating from non-arts subjects – hence an adjustment of fees according to future income/job prospects was debated. Recent student occupations at UCL's Slade and Cooper Union NYC for example, have illustrated the urgency with which artists appeal against rising HE costs.

Another interesting point was raised in relation to increasing the profile of the arts in non-arts sectors as a means to increase the exposure of artists to different social, political and economic contexts as well as providing non-artists an alternative way of knowledge exchange. This would increase the value of arts education, and provide artists with a variety of new professional horizons. An example of how this could come into action is currently piloted by Learning from Kilburn, a place making and collective learning initiative exploring the character of Kilburn in North-West London. The group concluded the discussion by raising concerns about the lack of public debate on arts education in general, as well as demanding an democratic approach to creative HE access.

Group 2) – What does it mean to experiment for experiment’s sake?

Within this group the focus was on discussing if it is still possible to be radical within the market driven stucture of the creative HEI's. With recent cuts to arts education, concerns were raised over the standardisation of assessment criteria and a lack of supervisor time, which often results in less individual support and an increasing homogenisation of artistic thought. For the group the term 'radical' described a process in which things are taken into different directions by pushing boundaries inside and outside of the institution. This requires space and time for experimentation in order to successfully challenge existing pre-occupations and learning objectives. How these aims can become reality depends on the flexibility of the HE structure, and how well it can be appropriate to facilitate a creative and alternative framework for knowledge exchange.

Group 3) – What does it mean to work within a group?

Here the aims was to critically engage with the possibilities of collaborative practices as facilitator of creative knowledge exchange. Based on the principle of participation, collaborative work offers a chance to be heard, but also to learn how to compromise ideas. Within HE however, hierarchies can become a problem in collectively developing and completing learning goals, in which some tasks might seem irrelevant and imposed to some students. The group argued that existing assessment criteria do not recognise the value of the creative process while only focusing on a final product. Collaborative practices however, thrive through process and offer flexible social structures that are often beneficial to mediating skills and knowledge.

Group 1) – What does it mean to put a monetary value on education?

This group discussed the importance of accessibly to and independence of arts education on the backdrop of soaring HE fees. The monetary value of arts education raises questions about the autonomy of how artistic knowledge is mediated. The Barbican in London for example supports the development of an East London alternative art school called Open School East which was launched in September 2013. Some participants criticised that this would increase the Barbican's cultural power by crucially determining the schools development (However, in what ways this influences the teaching curriculum and knowledge exchange structure is still to be evaluated). With this in mind some participants have argued that there should be the possibility for alternative or even free forms of creative HE. There was a strong consensus that the precarious work structures artists are exposed to after graduation put them at strong disadvantage compared to peers graduating from non-arts subjects – hence an adjustment of fees according to future income/job prospects was debated. Recent student occupations at UCL's Slade and Cooper Union NYC for example, have illustrated the urgency with which artists appeal against rising HE costs.

Another interesting point was raised in relation to increasing the profile of the arts in non-arts sectors as a means to increase the exposure of artists to different social, political and economic contexts as well as providing non-artists an alternative way of knowledge exchange. This would increase the value of arts education, and provide artists with a variety of new professional horizons. An example of how this could come into action is currently piloted by Learning from Kilburn, a place making and collective learning initiative exploring the character of Kilburn in North-West London. The group concluded the discussion by raising concerns about the lack of public debate on arts education in general, as well as demanding an democratic approach to creative HE access.

Group 2) – What does it mean to experiment for experiment’s sake?

Within this group the focus was on discussing if it is still possible to be radical within the market driven stucture of the creative HEI's. With recent cuts to arts education, concerns were raised over the standardisation of assessment criteria and a lack of supervisor time, which often results in less individual support and an increasing homogenisation of artistic thought. For the group the term 'radical' described a process in which things are taken into different directions by pushing boundaries inside and outside of the institution. This requires space and time for experimentation in order to successfully challenge existing pre-occupations and learning objectives. How these aims can become reality depends on the flexibility of the HE structure, and how well it can be appropriate to facilitate a creative and alternative framework for knowledge exchange.

Group 3) – What does it mean to work within a group?

Here the aims was to critically engage with the possibilities of collaborative practices as facilitator of creative knowledge exchange. Based on the principle of participation, collaborative work offers a chance to be heard, but also to learn how to compromise ideas. Within HE however, hierarchies can become a problem in collectively developing and completing learning goals, in which some tasks might seem irrelevant and imposed to some students. The group argued that existing assessment criteria do not recognise the value of the creative process while only focusing on a final product. Collaborative practices however, thrive through process and offer flexible social structures that are often beneficial to mediating skills and knowledge.

Interview with Anna Kontopoulou, ICA Student Forum Member

Anna is one of the organisers of the Radical Education Workshop. She is a member of the ICA Student Forum and a current PhD Student at the London Graduate School which is a programme offered by Kingston University London in collaboration with a selected panel of academics from universities in London and South-East England. Her PhD research focuses on the significance of curating an alternative kind of relative autonomy, looking at it from the standpoint of the Marxist notion of subsumption and surplus value. Anna has been looking in depth at the role of the curator in the political economy of contemporary art practices, particularly those influenced by relational aesthetics. She has also supplemented her Marxist analysis with Lacan’s theories of discourse to examine the increasing subsumption of art into University discourse that is rapidly becoming the primary form of validation of its social value.

Below she will briefly describe her engagement with the ICA Student Forum, as well as commenting on how she imagines the future of Radical Education.

Q1) Why did you join the ICA Student Forum and how do you benefit from your participation?

By joining the ICA student forum, I was hoping to meet like-minded people, like students from different colleges, and different levels, who would have similar frustrations like me and would meet to discuss them – expand my perspectives by meeting fellow artists and students, and engage in serious debates around ‘student’ issues. My philosophy faculty does not allow for much empirical knowledge or discussion around experience, dialogue and methodologies usually practiced in art, and thus I needed to connect back with art-minded people.

However, it is worth mentioning perhaps here, that the forum did not really function like this, until very recently, when we decided to work as a group for the first time (for the New Terms Radical Education Workshop). Before that, the work that was done, was mostly driven by individual career-oriented intentions, and as a response to the existing curatorial program of the museum. For this project however, we thought, since there will be so many fine art graduates from all around the UK represented here, but also visiting the space, why not attend to their needs, and accommodate an event for them. Focusing on what art students need to talk about instead of our own individual agendas. Some students focused on the events organised before us on the day entitled: New Terms: Reading Group, while other ICA Student Forum members focused on organising a party, Late Terms: Club Night

In general I have benefited from the forum, both at individual level, with being given the opportunity to curate my own program and practice out my theoretical investigations, but also as an individual within a group, attempting to engage in collaborative investigations and learn from each other. I am also very happy that I have somehow attempted to imagine a 'reclaiming' of the ICA as a space for public debate and action, not only with our most recent event, but also with previous events that I have curated there (like ‘Honk! If Your Body's not Yours') that opened up the debate to other not necessarily art related discourses.

It is true perhaps that social practices’ potential to enunciate alternative social and political forms, is limited, when these relations are situated and form part of the art institutional context. Especially if they remain as such, and there is no action outside it; social processes most often turning into their opposites altogether. At the same time however, museums still function as repositories of historical collective memory and sites of systemic historical comparison for the production of ‘contemporary’ taste, including knowledge and discourse. It is the museum, after all, that should first and foremost be a place for collective analysis, moving perhaps from symbolic participation to collective investigation. Where we are not only reminded of the egalitarian projects and movements of the past in a nostalgic kind of way, but also where we can learn how to discuss and communicate contemporary issues as they emerge outside hierarchical value systems, by activating these spaces for debate and collective action.

So, this is how I have tried to benefit from it. I have tried to open up the discourse to issues of political economy for example, organised discussions that attempt to tackle the issues of representation and move beyond it, by imagining a dialogue between organising and art. The ICA provides me with exposure to a wider middle class, mostly white platform, to address issues that are not necessarily addressed within it, and potentially move beyond the art public to a more open understanding of identification with a ‘general public’-who does that involve? what happens if we don’t identify with that?

Unfortunately, nowadays, taking into account how the art world operates today, the work of an artist no matter how ‘relational’ or ‘dialogical’ or socially enunciative and ‘inclusive’, unless it enters into the economy of circulation, it has no chance of validating its ‘social importance’. If there is no exposure there is no social validity, and thus any claim for free relational value is automatically extinguished. If we take into account the current trend for curatorial solidarity for resistance and the naive but at the same time genuinely motivated insistence by cultural workers on art’s value as enunciative tool for alternative social relations, the key task then becomes how can the curator continue managing the relationship between autonomous art and the culture industry, in the name of another kind of ‘relative’ autonomy that gets exposure in public space through its own laws of movement, but produces knowledge of the ‘symbolic’ part of participation (that is so often co-opted from base communities). This is what my aim is by using the ICA as a platform to experiment with that, by organising long term, open ended collaborative investigations. The paradox, of course, continues, as the ICA validates itself as a socially aware institution through works like this, but at least what escapes this subsumption is the the value form of our participation. The direct actions we take, and the commitment to come together and organise as a group. In short, our coming together. This is hopefully what remains outside the institutional form of exchange, as a relative autonomy of our value form of participation.

Q2) What are the reasons for you to initiate a forum around Radical Education? Why is it important for the field of the Cultural and Creative Industries right now?

I have kind of described the conditions in which the Radical Education workshop came about. The Radical Education workshop was initiated by a group of ICA members who wanted to work together on issues that concerned them as students, teachers and cultural producers around the state of arts education. My personal impetus for initiating this project comes from my frustration as a new ‘educator’ within an academic environment that does not allow space for any kind of ‘radical’ way of learning, even though the courses I am teaching, are all art related ones. It is also perhaps important to mention here, my own involvement with different radical groups around London, like RadEd and my interest in dialogical aesthetics in general.

More generally, if we consider the relationship between knowledge production and knowledge economization, how artistic knowledge is made subject to free trade by 'research' branding, and by implication considering the increasing subsumption of artistic 'knowledge' as new and 'original information' to be used by Culture and Creative Industry, then we can see how the relationship between autonomous art and culture industry involves a much more complex integrated kind of dialectic, where the two halves do not add up anymore. Art plays along its own subsumption into culture industry, where the institution needs to curate its autonomy, to preserve the ongoing illusion of a dialectic, university trains students to become curators of their own work, instead of allowing them to experiment for experiment's sake, and all that matters is a validation of art's 'contemporary' value. The artists intentions, the actual content or even what the work does, do not have real importance, as long as one can legitimise the 'relational' value of their project within the ‘contemporary’ ‘global community’ of ‘unified’ art world. The problem for me is that this ‘contemporaneity’ is not so synchronic as we want to make it. It is in fact a disjunctive synthesis of different times that depend on each other, and mutually form one another.

Any kind of dialogical aesthetic, radical education or alternative pedagogy project, or in fact any effort that attempts to counteract the 'cultural democracy' kind of didacticism that is involved in the institutionalised vertical kind of thinking (and learning), and its propagation of bourgeois ideologies from high to low, is very important in the wider project of a horizontal democratisation of culture.

Q3) What do you think Radical Education will look like in the near future? How can creative knowledge exchange become more radical?

I don't know, but I think it will involve a combination of direct action organising, as informed by grass roots and community organising strategies, but also informed by technological advancements in communication and information technologies. I fear that the act of talking, as in a physical encounter, listening to oneself listening to others, uttering and transferring affects to words, but also activating and performing a context, within a common space/time habitat might be subsumed by digital technology…

Creative knowledge exchange can become more radical, if more radical people are involved with it. We have a lot to learn from people whose lives are committed to make a change, and who have years of experience in organising. As well as by involving people who are not usually represented within the concept of the 'general public', and do not identify with any of the 'general public's ideologies’ or contemporary art discourse. And I risk sounding too adamant here, but it is only by organising space for dialogue with larger long term collectives that have developed strong positions of their political interests, and with individuals whose voice is usually excluded that we can learn to listen. And then we can talk. And then you have dialogue.

And in my opinion, any such emancipatory project should be a long term, open ended and collaborative investigation-based project, that comes out of genuine curiosity rather that 'social obligation', and whose terms are constantly undergoing revision (without 'evaluation'…).

(Photos and edited by Silvie Jacobi)

Below she will briefly describe her engagement with the ICA Student Forum, as well as commenting on how she imagines the future of Radical Education.

Q1) Why did you join the ICA Student Forum and how do you benefit from your participation?

By joining the ICA student forum, I was hoping to meet like-minded people, like students from different colleges, and different levels, who would have similar frustrations like me and would meet to discuss them – expand my perspectives by meeting fellow artists and students, and engage in serious debates around ‘student’ issues. My philosophy faculty does not allow for much empirical knowledge or discussion around experience, dialogue and methodologies usually practiced in art, and thus I needed to connect back with art-minded people.

However, it is worth mentioning perhaps here, that the forum did not really function like this, until very recently, when we decided to work as a group for the first time (for the New Terms Radical Education Workshop). Before that, the work that was done, was mostly driven by individual career-oriented intentions, and as a response to the existing curatorial program of the museum. For this project however, we thought, since there will be so many fine art graduates from all around the UK represented here, but also visiting the space, why not attend to their needs, and accommodate an event for them. Focusing on what art students need to talk about instead of our own individual agendas. Some students focused on the events organised before us on the day entitled: New Terms: Reading Group, while other ICA Student Forum members focused on organising a party, Late Terms: Club Night

In general I have benefited from the forum, both at individual level, with being given the opportunity to curate my own program and practice out my theoretical investigations, but also as an individual within a group, attempting to engage in collaborative investigations and learn from each other. I am also very happy that I have somehow attempted to imagine a 'reclaiming' of the ICA as a space for public debate and action, not only with our most recent event, but also with previous events that I have curated there (like ‘Honk! If Your Body's not Yours') that opened up the debate to other not necessarily art related discourses.

It is true perhaps that social practices’ potential to enunciate alternative social and political forms, is limited, when these relations are situated and form part of the art institutional context. Especially if they remain as such, and there is no action outside it; social processes most often turning into their opposites altogether. At the same time however, museums still function as repositories of historical collective memory and sites of systemic historical comparison for the production of ‘contemporary’ taste, including knowledge and discourse. It is the museum, after all, that should first and foremost be a place for collective analysis, moving perhaps from symbolic participation to collective investigation. Where we are not only reminded of the egalitarian projects and movements of the past in a nostalgic kind of way, but also where we can learn how to discuss and communicate contemporary issues as they emerge outside hierarchical value systems, by activating these spaces for debate and collective action.

So, this is how I have tried to benefit from it. I have tried to open up the discourse to issues of political economy for example, organised discussions that attempt to tackle the issues of representation and move beyond it, by imagining a dialogue between organising and art. The ICA provides me with exposure to a wider middle class, mostly white platform, to address issues that are not necessarily addressed within it, and potentially move beyond the art public to a more open understanding of identification with a ‘general public’-who does that involve? what happens if we don’t identify with that?

Unfortunately, nowadays, taking into account how the art world operates today, the work of an artist no matter how ‘relational’ or ‘dialogical’ or socially enunciative and ‘inclusive’, unless it enters into the economy of circulation, it has no chance of validating its ‘social importance’. If there is no exposure there is no social validity, and thus any claim for free relational value is automatically extinguished. If we take into account the current trend for curatorial solidarity for resistance and the naive but at the same time genuinely motivated insistence by cultural workers on art’s value as enunciative tool for alternative social relations, the key task then becomes how can the curator continue managing the relationship between autonomous art and the culture industry, in the name of another kind of ‘relative’ autonomy that gets exposure in public space through its own laws of movement, but produces knowledge of the ‘symbolic’ part of participation (that is so often co-opted from base communities). This is what my aim is by using the ICA as a platform to experiment with that, by organising long term, open ended collaborative investigations. The paradox, of course, continues, as the ICA validates itself as a socially aware institution through works like this, but at least what escapes this subsumption is the the value form of our participation. The direct actions we take, and the commitment to come together and organise as a group. In short, our coming together. This is hopefully what remains outside the institutional form of exchange, as a relative autonomy of our value form of participation.

Q2) What are the reasons for you to initiate a forum around Radical Education? Why is it important for the field of the Cultural and Creative Industries right now?

I have kind of described the conditions in which the Radical Education workshop came about. The Radical Education workshop was initiated by a group of ICA members who wanted to work together on issues that concerned them as students, teachers and cultural producers around the state of arts education. My personal impetus for initiating this project comes from my frustration as a new ‘educator’ within an academic environment that does not allow space for any kind of ‘radical’ way of learning, even though the courses I am teaching, are all art related ones. It is also perhaps important to mention here, my own involvement with different radical groups around London, like RadEd and my interest in dialogical aesthetics in general.

More generally, if we consider the relationship between knowledge production and knowledge economization, how artistic knowledge is made subject to free trade by 'research' branding, and by implication considering the increasing subsumption of artistic 'knowledge' as new and 'original information' to be used by Culture and Creative Industry, then we can see how the relationship between autonomous art and culture industry involves a much more complex integrated kind of dialectic, where the two halves do not add up anymore. Art plays along its own subsumption into culture industry, where the institution needs to curate its autonomy, to preserve the ongoing illusion of a dialectic, university trains students to become curators of their own work, instead of allowing them to experiment for experiment's sake, and all that matters is a validation of art's 'contemporary' value. The artists intentions, the actual content or even what the work does, do not have real importance, as long as one can legitimise the 'relational' value of their project within the ‘contemporary’ ‘global community’ of ‘unified’ art world. The problem for me is that this ‘contemporaneity’ is not so synchronic as we want to make it. It is in fact a disjunctive synthesis of different times that depend on each other, and mutually form one another.

Any kind of dialogical aesthetic, radical education or alternative pedagogy project, or in fact any effort that attempts to counteract the 'cultural democracy' kind of didacticism that is involved in the institutionalised vertical kind of thinking (and learning), and its propagation of bourgeois ideologies from high to low, is very important in the wider project of a horizontal democratisation of culture.

Q3) What do you think Radical Education will look like in the near future? How can creative knowledge exchange become more radical?

I don't know, but I think it will involve a combination of direct action organising, as informed by grass roots and community organising strategies, but also informed by technological advancements in communication and information technologies. I fear that the act of talking, as in a physical encounter, listening to oneself listening to others, uttering and transferring affects to words, but also activating and performing a context, within a common space/time habitat might be subsumed by digital technology…

Creative knowledge exchange can become more radical, if more radical people are involved with it. We have a lot to learn from people whose lives are committed to make a change, and who have years of experience in organising. As well as by involving people who are not usually represented within the concept of the 'general public', and do not identify with any of the 'general public's ideologies’ or contemporary art discourse. And I risk sounding too adamant here, but it is only by organising space for dialogue with larger long term collectives that have developed strong positions of their political interests, and with individuals whose voice is usually excluded that we can learn to listen. And then we can talk. And then you have dialogue.

And in my opinion, any such emancipatory project should be a long term, open ended and collaborative investigation-based project, that comes out of genuine curiosity rather that 'social obligation', and whose terms are constantly undergoing revision (without 'evaluation'…).

(Photos and edited by Silvie Jacobi)